History: US Business Operations with Nazi Germany

First published on February 11, 2021.

Among the Nazis’ first actions after taking power was to dismantle the German trade unions and labour power. By March 1933 the first concentration camp was erected at Dachau, soon to be followed by others, where numerous communists, socialists and other undesirables were interned. The German masses were thereafter transformed largely into devoted followers of Hitler, subjected regularly to Nazi propaganda; much of the techniques of which Gauleiter of Berlin Joseph Goebbels had learnt in the 1920s from Edward Bernays, the influential American propaganda merchant.

The Third Reich’s destruction of the left, along with Hitler’s stated intention to preserve big business, was welcomed by corporate managers. Before Hitler had even come to power, his views had drawn approval abroad from leading industrialists; like the American tycoon Irénée du Pont, a proponent of racial superiority and until 1925 the president of chemical multinational DuPont; and Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, a fervent anti-Semite who in the early 1920s wrote ‘The International Jew: The World’s Problem’.

A number of business moguls in America were overtly anti-Semitic, and Hitler’s rants against the supposed Jewish problem met with their approval. Ford’s writings in fact seem to have influenced Hitler and other Nazis like Baldur von Schirach, future head of the Hitler Youth. At the Nuremberg trials in May 1946, von Schirach said he had read Ford’s above work “and became anti-Semitic. In those days this book made such a deep impression on my friends and myself, because we saw in Henry Ford the representative of success”.

Ford himself was providing funds to the Nazi Party since the 1920s, when it was a miniscule political organisation (1). Hitler kept a life-size portrait of Ford behind his desk in Munich, and in 1931 the Nazi leader told a Detroit news reporter, “I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration”. Each year Ford also sent money to Hitler personally on his birthday through Swiss or Swedish banks, between around 10,000 to 20,000 Reichsmarks annually. These payments to Hitler continued until 1944, more than two years after the German declaration of war on America. (2)

However, as Hitler became chancellor on 30 January 1933, the Nazi Party’s coffers were virtually empty and large bills remained unpaid. Just a few weeks before, Goebbels complained in his diary that “financial troubles make all organised work impossible” and “the danger now exists of the whole party going to pieces” (3). This indicates that, up until Hitler took control, the Nazis received rather limited funding from big business. Greater contributions would be forthcoming, almost as soon as Hitler gained the chancellorship.

To help solve the Nazi Party’s financial plight and increase his grip on power, Hitler invited over 20 industrialists to attend a conference, on 20 February 1933, held at the official residence in Berlin of Hermann Göring. He was Hitler’s second-in-command, a morphine addict and President of the Reichstag. Among those who turned up at the meeting were well known individuals like Gustav Krupp (owner of the Krupp steel company); Fritz von Opel (Opel AG board member, grandson of founder Adam Opel); Georg von Schnitzler (IG Farben board member); Hjalmar Schacht (reinstated as Reichsbank president by Hitler in March 1933); and Albert Vögler (politician and businessman, centrally involved in arming the Wehrmacht).

Addressing the industrialists at length Hitler informed them, in a nutshell, that the choice now in Germany was between his rule – which respects the rights of private property and business – or that of communism, which he insisted would do the opposite and must be destroyed.

Highly impressed with Hitler’s speech, on behalf of the industrialists, Krupp expressed to the Nazi leader their “gratitude for having given us such a clear picture of his ideas”. Göring then informed Krupp and colleagues that the Nazi Party urgently required funds, to enable them to campaign sufficiently for the critical 5 March 1933 elections. The businessmen dispensed immediately with two million Reichsmarks (equivalent to about nine million Euro today). The notorious chemical corporation IG Farben, who we will come to later, provided the largest contribution to the Nazi Party at this meeting, giving 400,000 Reichsmarks. Further cash would be granted to the Nazis in coming days from German industry; while political opposition groups, such as the communists, were terrorised and intimidated by brown-shirted mobs.

The American historian Henry Ashby Turner, who has closely but skeptically analysed the links between German big business and the Nazis, acknowledged of the above funding, “These contributions unquestionably aided Hitler significantly” while Germany’s industrialists had always viewed the Weimar Republic “with misgiving”, primarily due to its accommodation of labour power. (4)

Goebbels wrote late in 1936 how Hitler confided to him that he had “wanted to shoot himself” in 1927, on account of having accumulated large debts. Coming to Hitler’s rescue was Emil Kirdorf, one of Germany’s foremost industrialists over the previous half century, who gave him 100,000 Reichsmarks (5). Kirdorf, who held far-right views, donated to the Nazi Party in the late 1920s; as too did another high level German businessman, the aforementioned Albert Vögler, founder of the United Steelworks (Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG).

By 1933 the Nazis were receiving funds not merely through German business, but also from investments arriving across the Atlantic. The New York Herald Tribune reported on 31 July 1941 that the Wall Street firm, Union Banking Corporation, which the American banker Prescott Bush was managing, had in 1933 sent $3 million to the Nazi Party. This is indeed the same Prescott Bush who was the father of George H. W. Bush, and grandfather to George W. Bush, both of whom would later become presidents.

Prescott Bush was a founder of the Union Banking Corporation in 1924, along with others like W. Averell Harriman, a wealthy businessman and future US Ambassador to the Soviet Union. Up until 1933, the Union Banking Corporation transferred an estimated total of $32 million to “Nazi bigwigs” in Germany, as noted by Moniz Bandeira, a prominent Brazilian historian. (6)

The Union Banking Corporation was closely connected to conglomerates owned by Fritz Thyssen, a German steel magnate and Nazi Party member since 1931, whose factories were an essential component of Hitler’s war industry. Thyssen supplied funds to the Nazis, both prior to and after their taking power. This money helped corrupt politicians like Göring to pursue luxurious lifestyles. Some of Thyssen’s cash funnelled to the Nazi Party went through “an account with a Dutch bank, which was interlocked with a Wall Street outfit called the Union Banking Corporation”. (7) (Preparata, Conjuring Hitler, p. 198)

Prescott Bush, a director and shareholder in the Union Banking Corporation and other Nazi-linked businesses, such as the Consolidated Silesian Steel Company (CSSC), had “played a central role in Hitler’s financing and armament”, according to two American historians who co-wrote a biography on George H. W. Bush, Webster Griffin Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin.

This is pertaining mostly to Prescott Bush’s connections to Thyssen, who had amassed great wealth through Hitler’s rearmament policies. Even after Hitler declared war on America in late 1941, and information began to leak out regarding Nazi crimes, Prescott Bush continued to work for firms like the Union Banking Corporation. A Guardian newspaper account outlined that he “profited from companies closely involved with the very German businesses that financed Hitler’s rise to power” (8). Union Banking Corporation’s assets were seized by the US government on 20 October 1942, under the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917.

For his share in the Union Banking Corporation, Prescott Bush received $1.5 million, equivalent to over $20 million today (9). Likewise having shares in this bank was E. Ronald Harriman, a US financier and younger brother of W. Averell Harriman, along with a couple of Nazi Party members (10). Moniz Bandeira wrote that the money earned by Prescott Bush here “allowed his son, George H. W. Bush, to set up the firms Bush-Obervey Oil Development Co., and Zapata Petroleum, later called Harbinger Group Inc., bringing together several companies to explore oil in the Gulf of Mexico and Cuba”.

Prescott Bush was also a director at the previously mentioned CSSC, a company which exploited resource rich Silesia in the Third Reich for the benefit of Hitler’s war machine. The CSSC used slave labour in the concentration camps, including Auschwitz. Another firm that Prescott Bush worked for, the New York-based Brown Brothers Harriman, served as a US business platform for the ubiquitous Thyssen. The founding partners of Brown Brothers Harriman included the two Harriman brothers and Prescott Bush. Both firms, the Union Banking Corporation and Brown Brothers Harriman, had during the 1930s according to the Guardian “bought and shipped millions of dollars of gold, fuel, steel, coal and US treasury bonds to Germany, both feeding and financing Hitler’s build-up to war”.

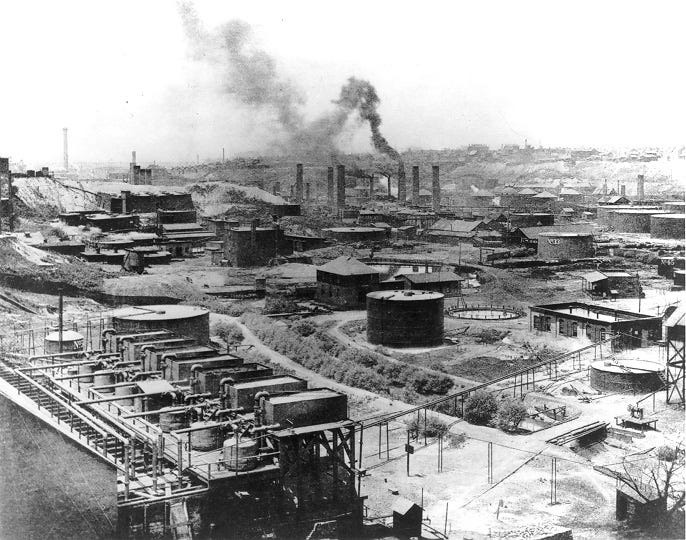

Some of America’s largest corporations had investments in Germany by the early 1930s, such as DuPont, General Electric, Gilette, Coca-Cola and Eastman Kodak. In the years ahead, many of these companies’ profits would grow substantially.

For example a Kodak branch in neutral Switzerland was, through 1942 and 1943, buying photographic equipment from Nazi Germany, Nazi-occupied France and also Hungary, allied to the Third Reich. America’s embassy in London described these dealings by Kodak as “fairly substantial purchases from enemy territory”. A separate Kodak branch in fascist Spain was purchasing goods from the Reich, such as in early 1942. The latter deal was defended by William Beaulac, the US chargé d’affaires in Madrid. (11)

Wall Street, the financial heartbeat of America, had looked on with some concern at the rise of communism. Its bankers instead viewed fascism overall rather favourably as avant-garde (12). When it became clear that Hitler was favourable to the status quo, while he wiped out labour influence, some Catholic, evangelical and even Jewish bankers connected to Wall Street engaged in business with the Nazis. They granted the Hitler regime about $7 billion in credit during the 1930s, as revealed in 1943 by George Seldes, a US investigative journalist. (13)

The historian Gaetano Salvemini, compelled to leave Mussolini’s Italy because of death threats, later said “almost 100% of American big business” was sympathetic towards Mussolini and Hitler’s dictatorships; because of their lucrative armament programs and destruction of labour.

One of the hallmarks of state capitalism is generating money through the business of war, as seen through the decades, with Western governments providing billions worth of weaponry to autocracies in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait and elsewhere.

The Nazis’ repressive policies enabled many companies linked to the Reich, such as Ford, to reduce their labour costs, from 15% of business volume in 1933 to just 11% in 1938. While Ford more than doubled their profits in Germany by 1939, they were also benefiting through a subsidiary in Nazi-occupied France, by posting earnings there of 58 million francs in 1941 alone. For this it received warm praise from Edsel Ford, president of the Ford Motor Company and son of founder Henry Ford.

By 1942 of the Wehrmacht’s 350,000 trucks in the field, around 120,000 of them were built by Ford factories in Germany (14). The General Motors-owned Opel plant in Rüsselsheim, western Germany, produced all-wheel-drive trucks for the Wehrmacht, which were most useful on the mud-soaked Eastern front and in the North African deserts.

On 13 December 1941, six days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, president Roosevelt issued a secret decree. He thereby granted special authorisation, so that certain US corporations could continue their business ventures with enemy nations, and with neutral countries on good terms with hostile states (15). This was a violation of the Trading with the Enemy Act; but Roosevelt, reliant on many of the same corporations in the prosecuting of war against Japan and Germany, was careful to appease big business. The American public had little idea of course that famous American companies, like Standard Oil, Ford, General Motors, and others were doing deals with the enemy.

The US manufacturing firm ITT – already involved through a German subsidiary (C. Lorenz AG) in producing Luftwaffe military aircraft with Focke-Wulf – was furthermore supplying high quality communications equipment to the Nazis, in conjunction with IBM, a US technology corporation. This had assisted in the synchronised Blitzkrieg warfare decisive to the Germans quickly defeating Poland, France, the Low Countries, and capturing parts of the western USSR. (16)

In late June 1940, Germany’s easy victory over France was celebrated by some US business leaders at dinners and parties held in New York, such as at the Waldorf Astoria hotel. Among those attending were the ITT founder and CEO, Sosthenes Behn, who had met Hitler in August 1933, James D. Mooney, a senior General Motors executive who saw Hitler on separate occasions, and Edsel Ford.

For their services to the Reich, Hitler lavished awards on Americans like Mooney and Henry Ford. At the beginning of Hitler’s rule US bankers flew to Nazi Germany, such as Winthrop Aldrich, chairman of Wall Street’s Chase National Bank. Aldrich met Hitler in the autumn of 1933, as too did Henry Mann of the National City Bank. Aldrich and Mann subsequently told William Dodd, the US Ambassador to Nazi Germany, that they were willing to “work with him [Hitler]”.

In August 1934 the US media tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who owned dozens of newspapers and magazines, visited Berlin to see Hitler. On returning home, Hearst described the dictator as “certainly an extraordinary man” and he wrote about Nazi Germany’s “great policy” and “great achievement” of saving Germany from communism.

During the late 1930s, the Ford Motor Company was shipping mineral resources to Nazi Germany, sometimes through its subsidiaries in third countries. At the start of 1937 for instance, Ford sent almost two million pounds of rubber and 130,000 pounds of copper to the Nazi regime (17). Ford retained a more than 50% share in their subsidiary in Cologne, Ford-Werke, following the December 1941 German announcement of hostilities against America.

Douglas Miller, America’s acting commercial attaché in Berlin, had predicted in 1935 that by 1937 the Nazis would be producing enough oil and gas out of soft coal “for a long war”. Miller revealed that the Standard Oil Company of New York was collaborating in these ventures by “furnishing millions of dollars to help”. (18)

Standard Oil, owned by the Rockefeller family, had sent $2 million to the Nazis as early as December 1933 – of which Ambassador Dodd in Berlin informed president Roosevelt during October 1936. Dodd also wrote to Roosevelt that Standard Oil “has made $500,000 a year in helping the Germans make ersatz gas for war purposes”. Standard Oil, along with other major US firms like DuPont, was working with IG Farben, the German chemical corporation. IG Farben was firmly incriminated in slave labour and the Holocaust, having provided the Nazis with the infamous poison gas Zyklon B, used to kill more than one million people at Auschwitz.

No less than 53 American companies had connections to IG Farben alone (19). At the Nuremberg trials, US judge Paul M. Hebert called IG Farben “one of Hitler’s greatest assets”.

From the mid-1930s, the Nazis had been hoarding imported oil in preparation for war – and considerable amounts of this vital resource was supplied to Hitler by American corporations, such as Standard Oil of New Jersey and Texaco, the latter company headquartered in Beaumont, Texas. Under Texaco’s pro-Nazi chairman Torkild Rieber, a Norwegian-American who was friends with Göring, the company made significant profits in granting oil to the Nazis.

After the start of European hostilities in September 1939, both Standard Oil and Texaco were supplying Nazi Germany with diesel fuel, lubricating oil and other petroleum substances (20). The Standard Oil and Texaco shipments to Germany came via ports in General Franco’s Spain. Through 1940 and 1941, American oil deliveries to Germany increased further, large amounts of which were sent into the Reich through US subsidiaries in neutral European countries. The Texaco chairman Rieber had illegally dispatched shipments of oil to Spain’s fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War, a factor in Franco’s eventual victory.

Ford and General Motors’ German subsidiaries, which together controlled 70% of the car market in Nazi Germany by 1939, were shifted increasingly towards producing military hardware. After all, even greater profits can be accrued from building the endless weapons of war. Ford and GM subsidiaries in the Reich built almost 90% of the Wehrmacht’s armoured “mule” three ton half-tracks, along with over 70% of Hitler’s medium and heavy-duty trucks. US intelligence reports highlighted this and stated that these vehicles served as “the backbone of the German Army transportation system”. (21)

The Belgian-born historian Jacques R. Pauwels wrote, “Many of Hitler’s wheels and wings were produced in the German subsidiaries of GM and Ford” and that “At one point, GM and Ford together reportedly accounted for no less than half of Germany’s entire production of tanks”.

The German Navy was supplied with some shipments of fuel by William Rhodes Davis, a Texan oil financier. In collaboration with US entrepreneur Fred Koch, father of future billionaires Charles and David Koch, Davis helped to build an oil refinery in Hamburg during the early stages of Hitler’s rule. This oil refinery became the third largest in the Reich, which refined high-octane oil for Luftwaffe warplanes. (22)

The American diplomat Dodd, who stepped down from his ambassadorship to Nazi Germany in December 1937, told the media the following month that US industrialists are “working closely with the fascist regimes in Germany and Italy. I have had plenty of opportunity, in my post in Berlin, to witness how close some of our American ruling families are to the Nazi regime”. (23)

In 1942 Standard Oil, through an independent headquarters in Switzerland, asked for authorisation to continue selling oil to Germany; on this occasion, from fields that Standard was exploiting in Romania, a country closely allied to Hitler under its dictator Ion Antonescu. Again in 1942 a Standard Oil subsidiary, the West India Oil Company – which was established to exploit raw materials in Cuba and elsewhere in the Caribbean – sent oil to the Reich through a firm located in Buenos Aires, called the Cia Argentina Comercial de Pesquería (24). A number of banking houses in Wall Street profited from doing business with the Nazis, such as the Bank of America (Forbes), Morgan Bank, Read & Co., and Chase Manhattan Bank.

Also pursuing business deals with the Reich were General Electric and the Dow Chemical Company. Dow Chemical, with its main headquarters in Michigan, conducted business with IG Farben, which was strongly supporting German rearmament. In 1934 and 1935, Dow Chemical delivered to IG Farben almost nine million pounds of magnesium, a substance used in airplane manufacturing, incendiary bombs and ammunition. IG Farben was granted this magnesium at a 30% lower cost, in comparison to Dow Chemical prices generally sold to American customers. (25)

During the war years, other US corporations were conducting covert business operations with the Nazis: such as Standard Oil of California, Phillips Petroleum, Mack Trucks and Firestone Tires, which had subsidiaries in neutral nations like Sweden and Switzerland. Many of their products, once completed in those countries, was sent to the Reich (26). After the Nazis became an official enemy of America from December 1941, General Motors and Ford among others continued dealing with Hitler. This was mainly through their German subsidiaries in Rüsselsheim or Brandenburg. General Motors’ Opel subsidiary in Brandenburg produced Junkers Ju-88 fighter aircraft, land mines, trucks and torpedo detonators for the German armed forces. By 1944 General Motors was still importing goods into Nazi Germany from another subsidiary based in Sweden. (27)

The US companies Chase National Bank, and National City Bank, developed ties with the Nazi-linked Bank for International Settlements (Bank für Internationalen Zahlungsausgleich). The latter bank, located in Basel, Switzerland, was involved in the transfer of gold that the Nazis had stolen from Jewish populations in Europe. The gold was melted down and marked with a date preceding World War II, in order to obscure its origins and be used freely by senior Nazis.

Between 1940 and 1946, the Bank für Internationalen president was Thomas H. McKittrick, a Harvard-educated American banker. In this position McKittrick became a Nazi stooge, as the Bank für Internationalen mediated business with the Axis countries; while it was effectively controlled by Nazi officials like Emil Puhl, vice-president of Germany’s Reichsbank and Walther Funk, the German Minister for Economic Affairs. Funk was later sentenced to life imprisonment at Nuremberg.

McKittrick was a friend of Allen Dulles, a US intelligence officer and future CIA director, whom he met in Switzerland where Dulles was stationed during the war. Dulles, also a corporate lawyer, previously met Hitler and Mussolini when acting as a legal adviser at the League of Nations.

After a business trip to Germany in 1935, Dulles was reportedly disturbed at the treatment of Jews (28). Allen, with his brother John Foster Dulles, were partners of Sullivan & Cromwell, a New York law firm which established a separate office in Berlin by 1928, but which closed in 1935. The Dulles brothers established contacts with various elites in Germany, including some Nazis (29). From 1933 onwards, Standard Oil and IG Farben were producing significant quantities of oil, gasoline and synthetic rubber for the Nazis from bituminous coal, through a hydrogenation process.

The furnishing of these important natural resources to the Nazi war machine, performed a role in enabling Hitler to swiftly defeat Poland; by his sending 5,000 gas and oil-guzzling panzers and Luftwaffe bombers across Polish territory. At the Nuremberg trials, Judge Hebert said that the German ability to continually produce synthetic rubber, of which Standard Oil and IG Farben were involved in, “made it possible for the Reich to carry on the war independently of foreign supplies”. (30)

Another crucial synthetic material, tetraethyl lead, assisted greatly in the high speed performance of Luftwaffe fighter aircraft. Tetraethyl lead was provided to the Germans in 1935 by a US fuel additive company, Ethyl Gmbh, a daughter firm of Standard Oil and General Motors and connected also to IG Farben. Tetraethyl lead was a key component concerning the whole concept of Blitzkrieg warfare. More than 30 years after the war Albert Speer, Hitler’s armaments minister from February 1942, said that without different types of synthetic fuel supplied by American companies Hitler “would never have considered invading Poland”. (31)

In early 1938, Standard Oil presented IG Farben with the complete technical details for the creation of butyl rubber – a superior type of synthetic rubber, made from petroleum, and that was used in tyre construction for Wehrmacht vehicles like trucks. Germany is a resource poor country, so the collaboration with US business was clearly important to the Nazi regime. By 1940 the Germans possessed 40,000 tons of synthetic rubber, increasing to 70,000 tons by 1941 as they attacked the Soviet Union.

General Motors’ fully-owned German subsidiary, Opel AG, controlled 50% of the automobile market in the Reich by 1935, making it the largest car manufacturer there. Along with Ford, Opel became one of Nazi Germany’s largest panzer producers (32). General Motors chairman Alfred P. Sloan, an American industralist, acknowledged by 1942 – with the US and Nazi Germany now at war – that GM’s entire investment with Opel “amounted to about $35 million” (today equivalent to over $550 million). In December 1941, at the time of the Pearl Harbour attack, Standard Oil had invested $120 million in the Reich (over $2 billion today).

American companies like Pratt & Whitney and Bendix Aviation, the latter of which General Motors had a controlling stock interest in, were selling military patents to German corporations embedded in war production, such as BMW and Siemens. This came to light through a 1940 US Senate investigation. That same year, in return for royalties, Bendix Aviation provided full data regarding aircraft and diesel engine starters to Bosch, a German technology company centrally involved in Nazi armaments production. Bendix had to bypass the British blockade of Germany to push through with the deal. (33)

Japanese professor of business history, Yuji Nishimuta, who has analysed US industrial ties to the Nazis, wrote that, “The German subsidiaries of American corporations formed an important, even essential element, in the so-called ‘miracle of the German economy’” from the period 1933 to 1939. During the months after Hitler’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, US dealings in Nazi Germany “did not change”, according to Nishimuta, as “big American business conducted, as it were, ‘joint business operations’ with the Nazi government through their German subsidiaries” (34). Problems in the relationship only surfaced following Hitler’s declaration of war on 11 December 1941, but even then, as discussed, various US business operations continued.

Notes

1 Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira, The World Disorder: US Hegemony, Proxy Wars, Terrorism and Humanitarian Catastrophes (Springer; 1st ed. 2019 edition, 4 Feb. 2019) p. 19

2 Ibid.

3 Trials of War Criminals Before The Nuremberg Military Tribunals, Under Control Council Law No. 10, Volume VII, October 1946-April 1949, p. 16

4 Henry Ashby Turner Jr., Big Business and the Rise of Hitler, Jstor, Oct. 1969, page 13 & 14 of 15

5 Peter Ross Range, The Unfathomable Ascent: How Hitler Came to Power (Little, Brown and Company, 11 Aug. 2020) Chapter 16, Impending Catastrophe

6 Bandeira, The World Disorder, p. 15

7 Guido Giacomo Preparata, Conjuring Hitler: How Britain and America Made the Third Reich (Pluto Press; Illustrated edition, 20 May 2005) p. 198

8 Ben Aris, Duncan Campbell, “How Bush’s grandfather helped Hitler’s rise to power”, The Guardian, 25 September 2004

9 Bandeira, The World Disorder, p. 16

10 John Simkin, “Prescott Bush”, Spartacus International, September 1997 (Updated January 2020)

11 John S. Friedman, “Kodak’s Nazi Connections”, The Nation, 8 March 2001

12 Bandeira, The World Disorder, p. 16

13 Ibid.

14 Yuji Nishimuta, Nazi Economy and U.S. Big Businesses – The Case of Ford Motor Co., Jstor, October 1995, p. 8 of 14

15 Jacques R. Pauwels, “Profits über Alles! American Corporations and Hitler”, Global Research, 7 June 2019

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Bandeira, The World Disorder, p. 18

19 Gabriel Kolko, American Business and Germany, 1930-1941, Jstor, Dec. 1962, page 7 of 16

20 Pauwels, Global Research, 7 June 2019

21 The Industrialization Reorganization Act: Hearings Before The Subcommittee On Antitrust And Monopoly, Of The Committee On The Judiciary United States Senate, 93rd Congress, Second Session, p. 22

22 National Public Radio, “Hidden History of Koch Brothers Traces Their Childhood And Political Rise”, 19 January 2016

23 Bandeira, The World Disorder, p. 19

24 Ibid, p. 18

25 Harry Aubrey Toulmin, Diary of Democracy: The Senate War Investigating Committee (Richard R. Smith; 1st edition, 1 Jan. 1947) p. 94

26 Bandeira, The World Disorder, p. 20

27 Ibid.

28 John Simkin, “Allen Dulles”, Spartacus International, September 1997 (Updated January 2020)

29 Pauwels, Global Research, 7 June 2019

30 Kolko, American Business and Germany, 1930-1941, p. 10

31 Pauwels, Global Research, 7 June 2019

32 Kolko, American Business and Germany, 1930-1941, p. 13

33 Ibid., p. 14

34 Yuji Nishimuta, Nazi Economy and U.S. Big Businesses, The Case of General Motors Corporation, Jstor, April/October 1996, p. 17 of 17

Copyright © Shane Quinn, 2023